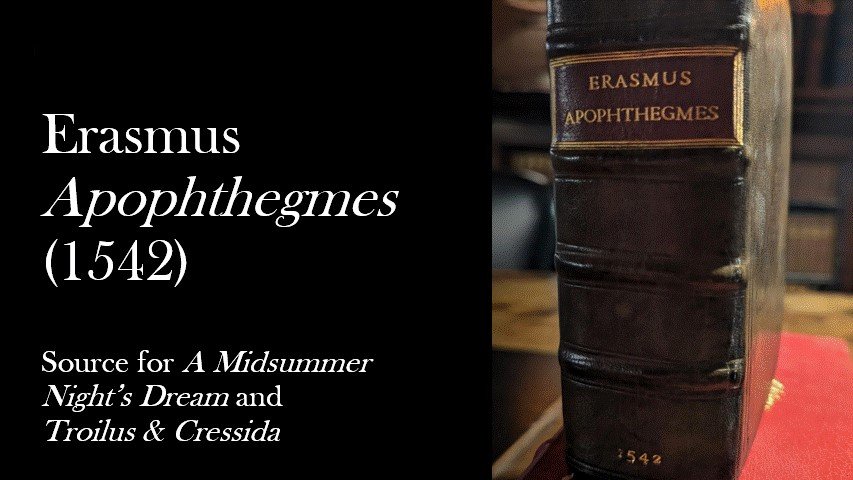

Erasmus' Apophthegmes (1542)

ERASMUS, Desiderius (1466-1536)

UDALL, Nicholas (1504-1556, Translator)

Apophthegmes. London: Richard Grafton, 1542

Apophthegmes, that is to saie, prompte, quicke, wittie and sentencious saiynges, of certain emperours, kynges, capitaines, philosophiers and oratours, aswell Grekes, as Romaines, bothe veraye pleasaunt [et] profitable to reade, partely for all maner of persones, [et] especially gentlemen. First gathered and compiled in Latine by the ryght famous clerke Maister Erasmus of Roterodame. And now translated into Englyshe by Nicolas Vdall. Excusum typis Ricardi Grafton, 1542. Cum priuilegio ad imprimendum solum.

Shakespeare frequently dipped into Erasmus' Apophthegmes or Adagia for sayings that appear in A Midsummer Night's Dream, Troilus & Cressida, As You Like It, and The Rape of Lucrece. See Emrys Jones, The Origins of Shakespeare (Oxford, 1977).

FIRST EDITION IN ENGLISH, translated by Nicolas Udall, black letter, lacks title (supplied in facsimile) and final 2 blanks, a few side-notes and headlines shaved, colophon mounted on stub, paper flaw touching one catch-word, modern calf antique.

Erasmus’s Apophthegmatum opus is a collection of adages and anecdotes from classical antiquity, modeled on Plutarch’s apophthegms in Moralia. The translator Nicholas Udall included numerous glossarial notes, lending his translation a pedagogical air. Udall was himself a schoolmaster, who was convicted for sexually assaulting his students, and a playwright, who wrote the early comedy Ralph Roister Doister. His translation of the Apophthegmes brought him to the attention of Queen Katherine Parr, who chose him to lead a team of scholars in translating The Paraphrase of Erasmus upon the New Testament.

The printer Richard Grafton’s career is an object lesson in the uncertainty of producing religious texts during the turbulent reign of Henry VIII. At the behest of Thomas Cromwell, Grafton and Edward Whitchurch published the “Matthew Bible” in 1537, followed by the “Great Bible,” the first authorized English translation of the Bible, in 1539. Following the execution of his patron Cromwell in 1540, Grafton found himself imprisoned three times between 1541-43 for printing material deemed hostile to the Crown, including “such bokes as wer thought to be unlawfull” such as the Great Bible, which faced a mixed reception under the post-Cromwell regime. He printed the Apophthegmes when he was released from prison in September of 1542.

In 1545, Grafton began printing material for Prince Edward and, following Henry’s death, became official printer to the new king. The political winds shifted again, however, after Edward’s death in 1553—a supporter of Lady Jane Grey, Grafton kept his head but lost his position as royal printer. He retired from printing to serve, at various times, as an MP, the warden of the Grocers’ Company, and the governor of the city’s hospitals. He passed on his types and woodcuts to his son-in-law, Richard Tottell. In 1557, Tottell printed the famous Songes and Sonnettes, better known as Tottel’s Miscellany, as well as the first English edition of the works of Sir Thomas More.

References: STC 10443; ESTC S105498

ERASMUS, Desiderius (1466-1536)

UDALL, Nicholas (1504-1556, Translator)

Apophthegmes. London: Richard Grafton, 1542

Apophthegmes, that is to saie, prompte, quicke, wittie and sentencious saiynges, of certain emperours, kynges, capitaines, philosophiers and oratours, aswell Grekes, as Romaines, bothe veraye pleasaunt [et] profitable to reade, partely for all maner of persones, [et] especially gentlemen. First gathered and compiled in Latine by the ryght famous clerke Maister Erasmus of Roterodame. And now translated into Englyshe by Nicolas Vdall. Excusum typis Ricardi Grafton, 1542. Cum priuilegio ad imprimendum solum.

Shakespeare frequently dipped into Erasmus' Apophthegmes or Adagia for sayings that appear in A Midsummer Night's Dream, Troilus & Cressida, As You Like It, and The Rape of Lucrece. See Emrys Jones, The Origins of Shakespeare (Oxford, 1977).

FIRST EDITION IN ENGLISH, translated by Nicolas Udall, black letter, lacks title (supplied in facsimile) and final 2 blanks, a few side-notes and headlines shaved, colophon mounted on stub, paper flaw touching one catch-word, modern calf antique.

Erasmus’s Apophthegmatum opus is a collection of adages and anecdotes from classical antiquity, modeled on Plutarch’s apophthegms in Moralia. The translator Nicholas Udall included numerous glossarial notes, lending his translation a pedagogical air. Udall was himself a schoolmaster, who was convicted for sexually assaulting his students, and a playwright, who wrote the early comedy Ralph Roister Doister. His translation of the Apophthegmes brought him to the attention of Queen Katherine Parr, who chose him to lead a team of scholars in translating The Paraphrase of Erasmus upon the New Testament.

The printer Richard Grafton’s career is an object lesson in the uncertainty of producing religious texts during the turbulent reign of Henry VIII. At the behest of Thomas Cromwell, Grafton and Edward Whitchurch published the “Matthew Bible” in 1537, followed by the “Great Bible,” the first authorized English translation of the Bible, in 1539. Following the execution of his patron Cromwell in 1540, Grafton found himself imprisoned three times between 1541-43 for printing material deemed hostile to the Crown, including “such bokes as wer thought to be unlawfull” such as the Great Bible, which faced a mixed reception under the post-Cromwell regime. He printed the Apophthegmes when he was released from prison in September of 1542.

In 1545, Grafton began printing material for Prince Edward and, following Henry’s death, became official printer to the new king. The political winds shifted again, however, after Edward’s death in 1553—a supporter of Lady Jane Grey, Grafton kept his head but lost his position as royal printer. He retired from printing to serve, at various times, as an MP, the warden of the Grocers’ Company, and the governor of the city’s hospitals. He passed on his types and woodcuts to his son-in-law, Richard Tottell. In 1557, Tottell printed the famous Songes and Sonnettes, better known as Tottel’s Miscellany, as well as the first English edition of the works of Sir Thomas More.

References: STC 10443; ESTC S105498

ERASMUS, Desiderius (1466-1536)

UDALL, Nicholas (1504-1556, Translator)

Apophthegmes. London: Richard Grafton, 1542

Apophthegmes, that is to saie, prompte, quicke, wittie and sentencious saiynges, of certain emperours, kynges, capitaines, philosophiers and oratours, aswell Grekes, as Romaines, bothe veraye pleasaunt [et] profitable to reade, partely for all maner of persones, [et] especially gentlemen. First gathered and compiled in Latine by the ryght famous clerke Maister Erasmus of Roterodame. And now translated into Englyshe by Nicolas Vdall. Excusum typis Ricardi Grafton, 1542. Cum priuilegio ad imprimendum solum.

Shakespeare frequently dipped into Erasmus' Apophthegmes or Adagia for sayings that appear in A Midsummer Night's Dream, Troilus & Cressida, As You Like It, and The Rape of Lucrece. See Emrys Jones, The Origins of Shakespeare (Oxford, 1977).

FIRST EDITION IN ENGLISH, translated by Nicolas Udall, black letter, lacks title (supplied in facsimile) and final 2 blanks, a few side-notes and headlines shaved, colophon mounted on stub, paper flaw touching one catch-word, modern calf antique.

Erasmus’s Apophthegmatum opus is a collection of adages and anecdotes from classical antiquity, modeled on Plutarch’s apophthegms in Moralia. The translator Nicholas Udall included numerous glossarial notes, lending his translation a pedagogical air. Udall was himself a schoolmaster, who was convicted for sexually assaulting his students, and a playwright, who wrote the early comedy Ralph Roister Doister. His translation of the Apophthegmes brought him to the attention of Queen Katherine Parr, who chose him to lead a team of scholars in translating The Paraphrase of Erasmus upon the New Testament.

The printer Richard Grafton’s career is an object lesson in the uncertainty of producing religious texts during the turbulent reign of Henry VIII. At the behest of Thomas Cromwell, Grafton and Edward Whitchurch published the “Matthew Bible” in 1537, followed by the “Great Bible,” the first authorized English translation of the Bible, in 1539. Following the execution of his patron Cromwell in 1540, Grafton found himself imprisoned three times between 1541-43 for printing material deemed hostile to the Crown, including “such bokes as wer thought to be unlawfull” such as the Great Bible, which faced a mixed reception under the post-Cromwell regime. He printed the Apophthegmes when he was released from prison in September of 1542.

In 1545, Grafton began printing material for Prince Edward and, following Henry’s death, became official printer to the new king. The political winds shifted again, however, after Edward’s death in 1553—a supporter of Lady Jane Grey, Grafton kept his head but lost his position as royal printer. He retired from printing to serve, at various times, as an MP, the warden of the Grocers’ Company, and the governor of the city’s hospitals. He passed on his types and woodcuts to his son-in-law, Richard Tottell. In 1557, Tottell printed the famous Songes and Sonnettes, better known as Tottel’s Miscellany, as well as the first English edition of the works of Sir Thomas More.

References: STC 10443; ESTC S105498